BÖËNA ARTICLE

Böëna Funds ‘Raising Coral’ Project

to Restore Health of Costa Rican Reefs

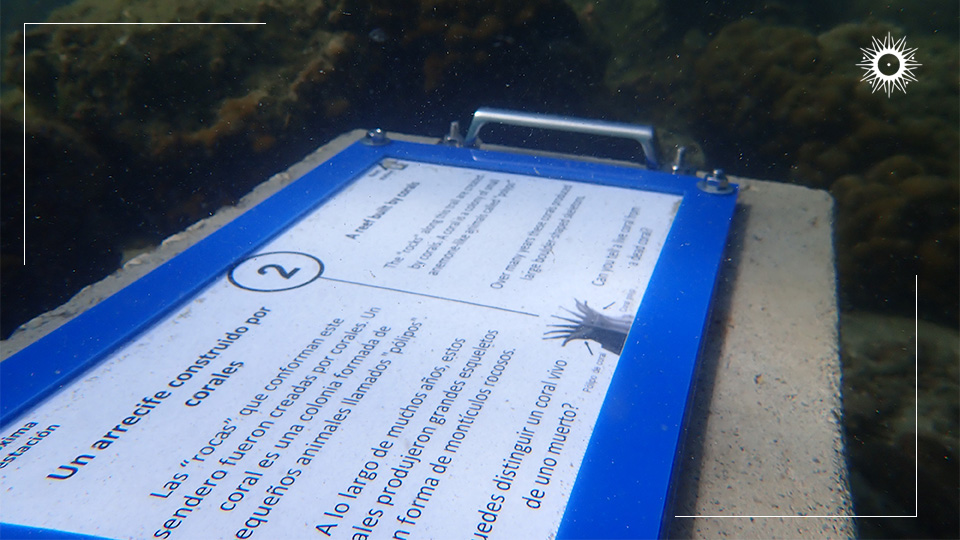

Consider the lowly coral. Actually an animal, it looks like a plant, as it never goes anywhere, and it usually reproduces asexually, which doesn’t sound very romantic.

Yet the humble coral provides shelter and food to a vast array of marine species at the critical base of the food chain. And that’s why Böëna Lodges is providing crucial financial support to Raising Coral, a one-of-a-kind nonprofit in Costa Rica dedicated to the restoration of these vital marine environments.

“Corals are the engineers of the ecosystems,” says Tatiana Villalobos, 31, the project manager for Raising Coral. “We can compare them with the trees of the rainforest, or even where houses are built in a city. So where you have corals, you have habitat, you have food available for different species.”

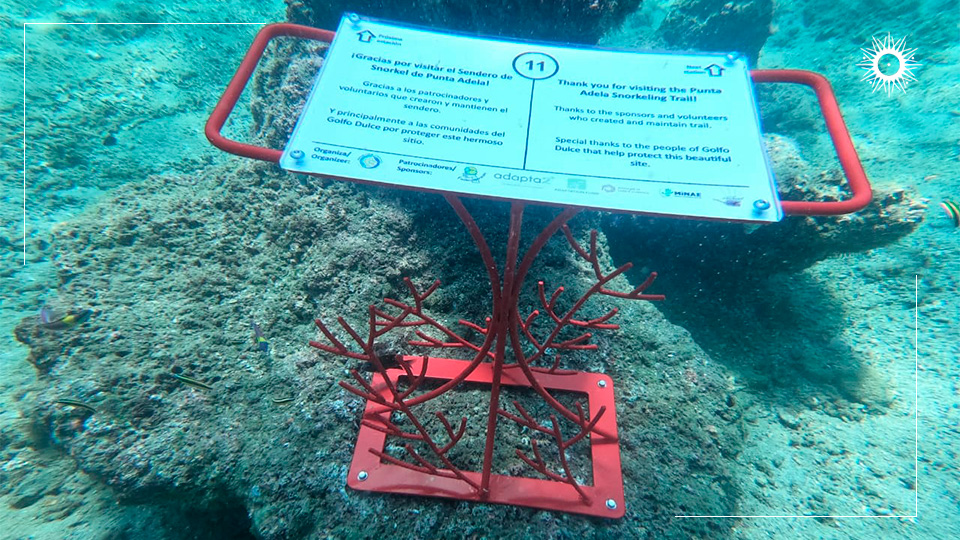

Tatiana, 31, born in San Ramón but currently living in Puerto Jiménez, is a scuba-diving marine and coastal manager who supervises teams of “coral gardeners” at the northern end of the Golfo Dulce, in southwestern Costa Rica.

“Corals are the perfect nursery for little fishes,” she says. “Mangroves and coral reefs are really, really important for the little ones. When you go, you can see all those colors. If you’re a mama, you probably really want to be able to leave your babies in places where they will be able to hide, or to be protected by themselves just with the structure.”

|

|

If you ever saw Pixar’s Finding Nemo, you would know that the titular clown fish would have been just fine had he never ventured outside the coral reef.

The corals attract plants like algae and sponges, and soon there are minnows nibbling at these plants, and then there are larger fish eating these smaller fish, and soon larger fish eating THESE smaller fish. An estimated 25% of all fish in the ocean depend in some way on coral reefs.

Coral reefs also protect coastlines from erosion and storms, and are a source of food and medicine. They attract scuba divers, snorkelers and anglers, providing jobs for locals. According to NOAA, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the net economic value of the world’s coral reefs is estimated to be close to tens of billions of dollars a year.

We also have corals to thank, in part, for our white beaches.

|

|

Böëna’s contribution

Lapa Rios, a Böëna property on the southern tip of the Osa Peninsula, latched onto this project under the guidance of Priscilla Murillo, the sustainability coordinator for this unique collection of five ecolodges.

“This is a monthly economic donation and an arrangement for logistics, food and human resources,” said Priscilla. “All this to promote experimental research into the genetic diversity of corals.”

Tatiana said the boats and the divers have to go out about five or six times a month to tend their gardens. She said Böëna Lodges has committed to pay for one of these monthly dives for the next year, paying for four coral gardeners, the boat, the dive equipment and the lunch. She believes this will be an important contribution to the science of restoring coral reefs in Costa Rica.

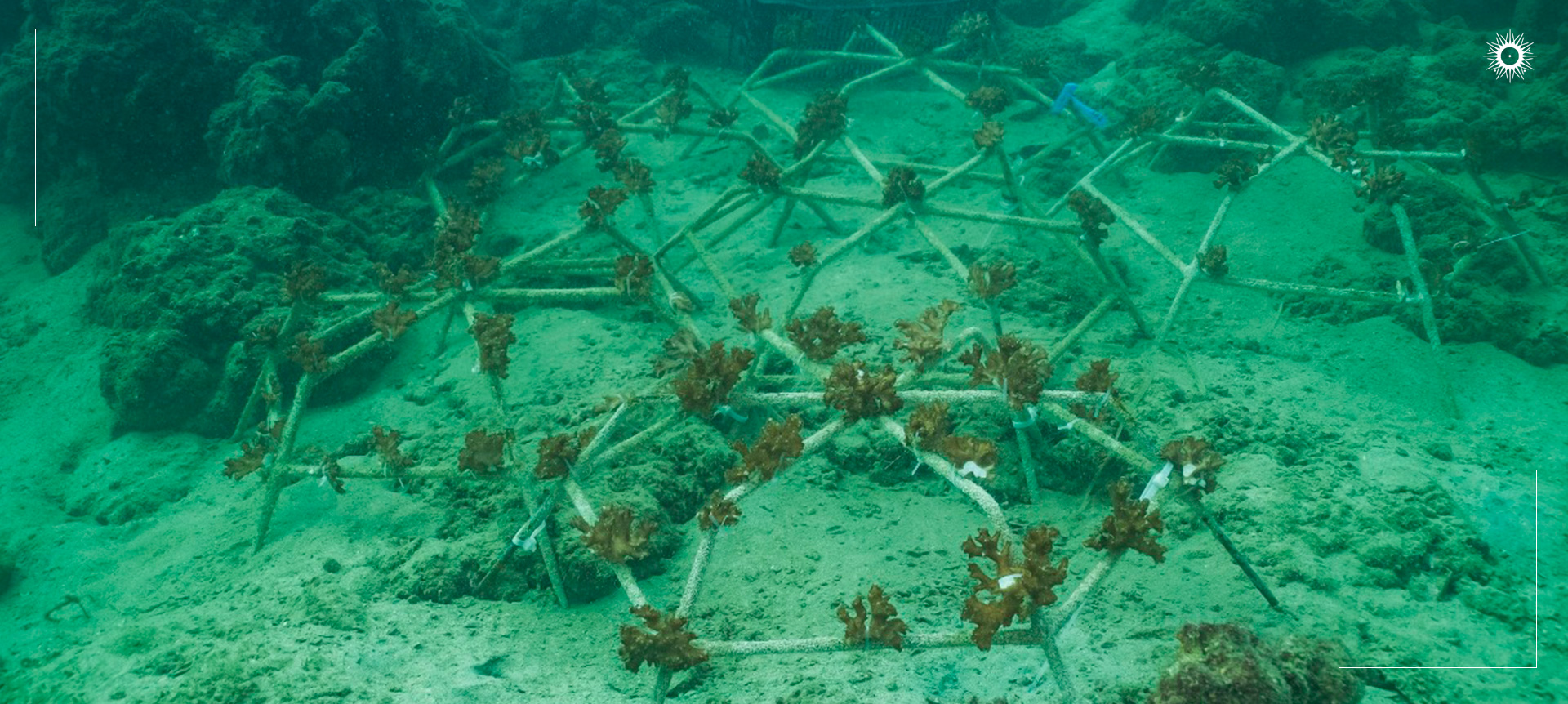

The “coral gardeners” get up early in the morning to catch their boat from Jiménez. They ride to the northern part of the Golfo Dulce, put on scuba equipment to jump in the water to tend their underwater coral gardens.

“Most of the gardeners are women, amas de casa [housewives],” says Tatiana. “Or the guys we have work as tourism guides or in sportfishing. So it becomes a complementary salary for these people.”

The divers harvest a small amount of coral from thriving colonies, less than 10 percent. Then they move this coral elsewhere to replant it in a “nursery” in a different part of the gulf. Nine months to a year later, when these replanted corals are thriving, the divers move them to a more auspicious location.

|

|

The Golfo Dulce project builds on similar work done earlier on Costa Rica’s Caribbean coast.

“We took really good data, we know the main coral reef builder species, we know the best techniques for growing these corals underwater, and also how to decrease stress or problems when we are doing all of this,” Tatiana says.

“Restoration means a lot of investment. There’s a lot of science behind it, and not everybody does science-based work. But it’s a lot of time, people, money and everything.”

The human aspects of the work are very important, she says.

“It’s more than corals. We have the fishermen, we have communities that are living there where the corals are. So the restoration, conservation, management of ecosystems is not going to be successful until we integrate local people, we make them understand what we are doing, and hopefully they can receive direct benefits from what we’re doing.”